In the glitzy world of Patagonian vest-wearing venture capitalists, where billion-dollar valuations and unicorn founders dominate headlines, an unspoken reality lurks behind the term sheets and fund announcements.

Venture capital isn’t always about building great companies. Often, it’s about looking like you did. And in that game, fund managers can win handsomely even if the startups they back don’t.

The Incentive Problem: Profits Without Performance

The venture model is designed around a management fee and carry structure. On paper, that aligns incentives: fund managers get a small annual fee (typically 2%) to operate the fund, and only earn the bulk of their compensation (the 20% "carry") after all investor capital has been fully returned and the fund turns a profit.

But here’s the catch: that 2% fee is charged on the total fund size. For a $100M fund, that’s $2M annually in fees. Money that covers salaries, travel, and overhead regardless of whether a single investment ever returns a dime.

Over a 10-year fund life, that adds up to 20% of the fund paid out in fees, even if the fund performs poorly. A fund manager can earn millions while delivering zero value to LPs (limited partners).

The Mark-Up Mirage: Paper Gains Over Real Returns

Worse yet, the industry thrives on paper gains (or unrealized gains), not cash-on-cash returns.

Since fund performance is often measured by interim metrics like TVPI (Total Value to Paid-In) or IRR (Internal Rate of Return), GPs (General Partners or fund managers) are incentivized to inflate the valuation of portfolio companies, and it’s especially easy to do if they're the ones leading the next round.

Here’s how the game is played:

Fund A invests in a startup’s seed round at a $5M valuation.

A year later, Fund A leads the Series A at a $15M valuation.

Voila! On paper, the seed investment just tripled in value.

No outside investors. No market validation. Just a circular mark-up that makes Fund A look good on paper.

These inflated valuations give the illusion of success, even when the underlying companies are stagnating. Or worse, silently failing.

AUM and the Pyramid Scheme Illusion

Here’s where the structure becomes pyramid-like.

VCs rarely make money from carry alone, and if they do it’s a long term game. The real play is to raise subsequent, increasingly larger funds, with each new fund earning more in management fees.

This creates a flywheel that resembles a soft Ponzi scheme:

Raise Fund I and deploy capital.

Mark up some early investments.

Show strong paper returns.

Use inflated metrics to raise Fund II—larger and more prestigious.

Repeat with Fund III, Fund IV...

Fund manager’s prestige and influence is measured not by DPI or liquidity, but by Assets Under Management (AUM). The more you manage, the more legitimate you appear, even if none of your companies have exited. The whole ecosystem begins to orbit around perception instead of performance.

Later funds rely on the narrative of earlier success, without actual exits, creating a structure where appearance drives capital, not results.

That is the pyramid.

The Deployment Illusion: Fund 2 Raised Before Fund 1 is Proven

Timing further distorts the picture.

The average VC fund takes 2.5 to 3 years to fully deploy capital, depending on strategy and stage. But most firms begin raising their next fund after just 18-24 months. Often before any material exits or even significant traction from Fund I investments.

That means Fund II is marketed based on:

Paper markups

Anecdotal traction

And the fund manager’s storytelling ability

By the time actual performance from Fund I is visible (typically 5–7 years in) it’s too late. The next two funds have already been raised. Many LPs are three funds deep before any DPI is shown.

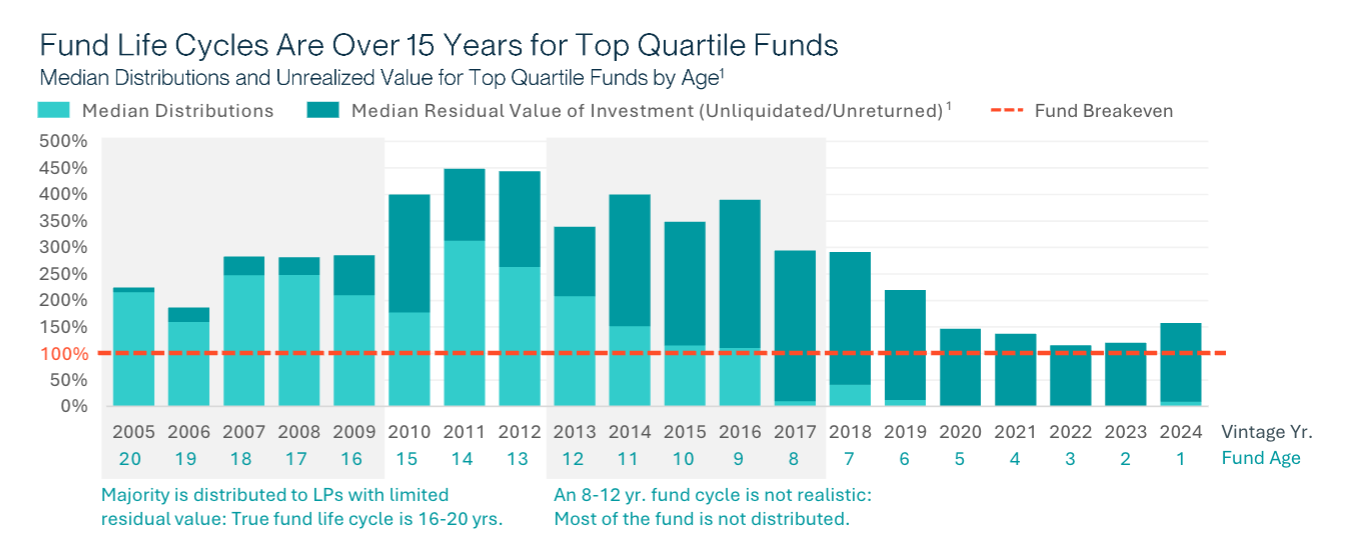

This further enables the game of growth for growth’s sake, not returns. Even among top quartile funds, the 100% DPI breakeven line isn’t consistently crossed until year 12 or later. Some distributions stretch well into years 15–20, making the typical 10-year fund cycle more of a fantasy than a financial reality.

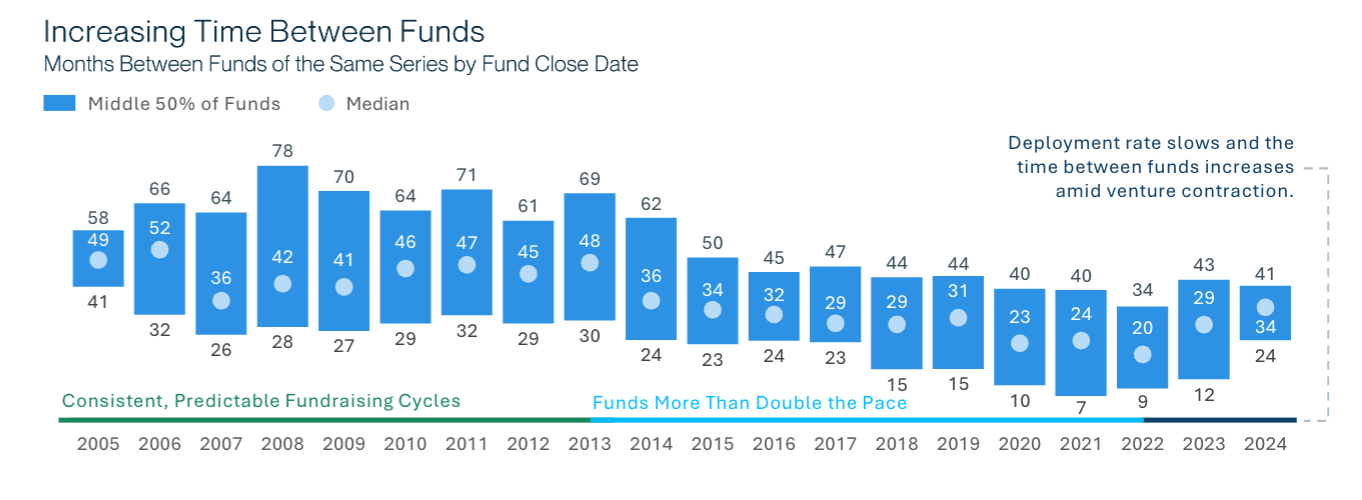

Meanwhile, despite that long maturity window, median time between funds dropped to as low as 15–24 months for much of the last decade—doubling the pace of capital raised relative to capital returned. Only recently has that trend begun to slow as the market contracts.

It’s a feedback loop of timing arbitrage. Managers capitalize on the long maturation period of venture investments to get ahead of reality, and ahead of accountability.

The Real Costs: Founders and LPs Lose

This model distorts the startup ecosystem in profound ways:

Founders are pushed into unnatural valuations, forced to chase unsustainable growth to justify inflated pricing.

LPs end up backing funds with poor real returns because they rely on paper gains and peer herd behavior.

The market gets flooded with overvalued companies and underwhelming outcomes.

Founders are particularly vulnerable. When their company gets marked up too quickly:

Their next round becomes harder to raise.

Their employees are underwater on options.

They face pressure to "grow into" a valuation they never asked for.

What Needs to Change

There are a few potential fixes:

DPI (Distributions to Paid-In) should be the gold standard for judging performance, not just IRR or TVPI. DPI cannot be faked. It reflects real cash returned, not hypothetical gains.

Third-party valuations should be required for internal mark-ups, especially when the same fund leads multiple rounds. There are a lot of funds that refuse to lead subsequent rounds for exactly this reason.

LPs need to demand transparency, and stop rewarding funds for paper performance. Chasing headline multiples instead of returns only perpetuates the problem.

Founders should push back against valuation games that don’t serve long-term success. An impressive cap table today isn’t worth a broken one tomorrow.

Until then, we’ll keep seeing a venture world where:

Success is measured by AUM, not ROI.

Momentum is manufactured, not earned.

And the smartest players win not by building great companies, but by navigating the fundraising treadmill better than their peers.

How ASE Does It Differently

At Ag Startup Engine (ASE), we’re intentionally building a different model. We’re not perfect and still learning but we’re being mindful of the traps that are easy to fall into and making conscious efforts to avoid them.

We’re not here to chase AUM growth, inflate valuations, or raise ever-larger funds disconnected from performance. Instead, our approach is intentionally disciplined, transparent, and long-term focused.

1. Slow and Intentional Deployment

Unlike traditional VCs that rush to deploy capital in 18–24 months, we take our time, deploying over five years, with annual capital calls aligned to real opportunity, not artificial urgency. This longer time horizon allows us to make better decisions, avoid hype cycles, and focus on founders building real businesses.

2. Proof Before Promises

We don’t raise the next fund based on paper markups. We raise based on actual outcomes. Our first fund ($1M) was fully deployed with meaningful returns before Fund 2 fundraising conversation began. Only after proving results did we raise Fund II ($3.3M)—now 80% deployed, with cash back to LPs already.

We’re currently raising a third follow-on fund (will close at ~$10M), not because we’re chasing AUM growth, but because we have the deal flow, the discipline, and the proof of performance to do it responsibly.

3. No Management Fee Games

Could we collect more management fees by raising bigger funds? Sure. But that’s not why we’re here.

We started ASE to back real solutions for agriculture and to build a community that moves the industry forward. The reality is: massive funds may look great on pitch decks, but they rarely generate consistent returns, especially in AgTech, where exit paths are slower and more nuanced.

We measure our success not by how much we raise, but by how our founders are improving the industry and how much we return to LPs.

4. Alignment with Founders and LPs

We don’t play valuation optics games. We aim for true market validation, not vanity metrics.

We also counsel founders directly on setting realistic valuations and fundraising goals. In a market where founders are often encouraged to chase inflated numbers, we work with them to build healthy cap tables and fundraise strategies that support long-term success.

That perspective is rooted in experience: every ASE manager has been, or is, a founder. We’ve made payroll during tight quarters, negotiated dilution tradeoffs, and navigated the emotional weight of building. That experience builds trust, and helps us deliver guidance that’s practical, not theoretical.

We believe that alignment across founders, fund managers, and LPs is critical, and we structure our capital and support accordingly.

Conclusion:

Venture capital is full of great investors doing good work and many rethinking their approach with evergreen funds and creative investment strategies.

But the system enables far too many to win without delivering real results. Until we shift the culture from growth at all costs to returns with accountability, the pyramid will keep growing, and founders and LPs will be left holding the bag.

So many astute points said exceptionally well!

Not sure you’re getting invited to the next VC Friday Drinks. Finally somebody has revealed what a shell game it all is.